Los Viajes De Gulliver Pdf Libro

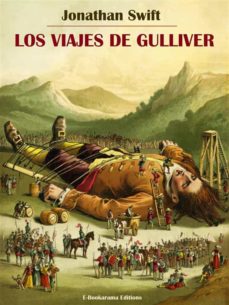

823.5TextatGulliver's Travels, or Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships is a prose of 1726 by the writer and clergyman, satirising both and the literary subgenre.

It is Swift's best known full-length work, and a classic of. Swift claimed that he wrote Gulliver's Travels 'to vex the world rather than divert it'.The book was an immediate success. Remarked 'It is universally read, from the to the nursery.' In 2015, released his selection list of 100 best novels of all time in which Gulliver’s Travels is listed as 'a satirical masterpiece'. Mural depicting Gulliver surrounded by citizens of Lilliput.The travel begins with a short preamble in which gives a brief outline of his life and history before his voyages.During his first voyage, Gulliver is washed ashore after a shipwreck and finds himself a prisoner of a race of tiny people, less than 6 inches (15 cm) tall, who are inhabitants of the island country of. After giving assurances of his good behaviour, he is given a residence in Lilliput and becomes a favourite of the Lilliput. He is also given permission by the King of Lilliput to go around the city on condition that he must not hurt their subjects.At first, the Lilliputians are hospitable to Gulliver, but they are also wary of the threat that his size poses to them.

The Lilliputians reveal themselves to be a people who put great emphasis on trivial matters. For example, which end of an egg a person cracks becomes the basis of a deep political rift within that nation. They are a people who revel in displays of authority and performances of power. Gulliver assists the Lilliputians to subdue their neighbours the Blefuscudians by stealing their fleet.

However, he refuses to reduce the island nation of Blefuscu to a province of Lilliput, displeasing the King and the royal court.Gulliver is charged with treason for, among other crimes, urinating in the capital though he was putting out a fire. He is convicted and sentenced to be blinded. With the assistance of a kind friend, 'a considerable person at court', he escapes to Blefuscu. Here, he spots and retrieves an abandoned boat and sails out to be rescued by a passing ship, which safely takes him back home.Part II: A Voyage to Brobdingnag 20 June 1702 – 3 June 1706. Gulliver exhibited to the Brobdingnag Farmer (painting by )Gulliver soon sets out again. When the sailing ship Adventure is blown off course by storms and forced to sail for land in search of fresh water, Gulliver is abandoned by his companions and left on a peninsula on the western coast of the continent.The grass of is as tall as a tree. He is then found by a farmer who is about 72 ft (22 m) tall, judging from Gulliver estimating the man's step being 10 yards (9 m).

The farmer brings Gulliver home, and his daughter cares for Gulliver. The farmer treats him as a curiosity and exhibits him for money. After a while the constant display makes Gulliver sick, and the farmer sells him to the Queen of the realm. Glumdalclitch (who accompanied her father while exhibiting Gulliver) is taken into the Queen's service to take care of the tiny man. Since Gulliver is too small to use their huge chairs, beds, knives and forks, the Queen commissions a small house to be built for him so that he can be carried around in it; this is referred to as his 'travelling box'.Between small adventures such as fighting giant and being carried to the roof by a, he discusses the state of Europe with the King of Brobdingnag. The King is not happy with Gulliver's accounts of Europe, especially upon learning of the use of guns and cannons.

On a trip to the seaside, his traveling box is seized by a giant eagle which drops Gulliver and his box into the sea where he is picked up by sailors who return him to England.Part III: A Voyage to Laputa, Balnibarbi, Luggnagg, Glubbdubdrib and Japan. Gulliver discovers Laputa, the flying island (illustration by )Setting out again, Gulliver's ship is attacked by, and he is close to a desolate rocky island near. He is rescued by the of, a kingdom devoted to the arts of music, mathematics, and astronomy but unable to use them for practical ends. Rather than use armies, Laputa has a custom of throwing rocks down at rebellious cities on the ground.Gulliver tours, the kingdom ruled from Laputa, as the guest of a low-ranking courtier and sees the ruin brought about by the blind pursuit of science without practical results, in a satire on bureaucracy and on the and its experiments. At the Grand Academy of in Balnibarbi, great resources and manpower are employed on researching preposterous schemes such as extracting sunbeams from cucumbers, softening marble for use in pillows, learning how to mix paint by smell, and uncovering political conspiracies by examining the excrement of suspicious persons (see ).

Gulliver is then taken to, the main port of Balnibarbi, to await a trader who can take him on to Japan.While waiting for a passage, Gulliver takes a short side-trip to the island of which is southwest of Balnibarbi. On Glubbdubdrib, he visits a magician's dwelling and discusses history with the ghosts of historical figures, the most obvious restatement of the 'ancients versus moderns' theme in the book. The ghosts consist of, and.On the island of, he encounters the, people who are immortal.

They do not have the gift of eternal youth, but suffer the infirmities of old age and are considered legally dead at the age of eighty.After reaching, Gulliver asks 'to excuse my performing the ceremony imposed upon my countrymen of ', which the Emperor does. Gulliver returns home, determined to stay there for the rest of his days.Part IV: A Voyage to the Land of the Houyhnhnms 7 September 1710 – 5 December 1715.

Gulliver in discussion with Houyhnhnms (1856 illustration by ).Despite his earlier intention of remaining at home, Gulliver returns to sea as the captain of a, as he is bored with his employment as a surgeon. On this voyage, he is forced to find new additions to his crew who, he believes, have turned against him. His crew then commits mutiny. After keeping him contained for some time, they resolve to leave him on the first piece of land they come across, and continue as pirates. He is abandoned in a landing boat and comes upon a race of deformed savage humanoid creatures to which he conceives a violent antipathy. Shortly afterwards, he meets the, a race of talking horses. They are the rulers while the deformed creatures that resemble human beings are called.Gulliver becomes a member of a horse's household and comes to both admire and emulate the Houyhnhnms and their way of life, rejecting his fellow humans as merely Yahoos endowed with some semblance of reason which they only use to exacerbate and add to the vices Nature gave them.

However, an Assembly of the Houyhnhnms rules that Gulliver, a Yahoo with some semblance of reason, is a danger to their civilization and commands him to swim back to the land that he came from. Gulliver's 'Master,' the Houyhnhnm who took him into his household, buys him time to create a canoe to make his departure easier. After another disastrous voyage, he is rescued against his will by a Portuguese ship. He is disgusted to see that Captain Pedro de Mendez, whom he considers a Yahoo, is a wise, courteous, and generous person.He returns to his home in England, but is unable to reconcile himself to living among 'Yahoos' and becomes a recluse, remaining in his house, avoiding his family and his wife, and spending several hours a day speaking with the horses in his stables.Composition and history It is uncertain exactly when Swift started writing Gulliver's Travels. (Much of the writing was done at Loughry Manor in, whilst Swift stayed there.) Some sources suggest as early as 1713 when Swift, Gay, Pope, and others formed the with the aim of satirising popular literary genres.

According to these accounts, Swift was charged with writing the memoirs of the club's imaginary author, Martinus Scriblerus, and also with satirising the 'travellers' tales' literary subgenre. It is known from Swift's correspondence that the composition proper began in 1720 with the mirror-themed Parts I and II written first, Part IV next in 1723 and Part III written in 1724; but amendments were made even while Swift was writing. By August 1725 the book was complete; and as Gulliver's Travels was a transparently anti- satire, it is likely that Swift had the manuscript copied so that his handwriting could not be used as evidence if a prosecution should arise, as had happened in the case of some of his Irish (the Drapier's Letters). In March 1726 Swift travelled to London to have his work published; the manuscript was secretly delivered to the publisher, who used five printing houses to speed production and avoid piracy.

Motte, recognising a best-seller but fearing prosecution, cut or altered the worst offending passages (such as the descriptions of the court contests in Lilliput and the rebellion of ), added some material in defence of Queen Anne to Part II, and published it. The first edition was released in two volumes on 28 October 1726, priced at 8 s.

6d.Motte published Gulliver's Travels anonymously, and as was often the way with fashionable works, several follow-ups ( Memoirs of the Court of Lilliput), parodies ( Two Lilliputian Odes, The first on the Famous Engine With Which Captain Gulliver extinguish'd the Palace Fire.) and 'keys' ( Gulliver Decipher'd and Lemuel Gulliver's Travels into Several Remote Regions of the World Compendiously Methodiz'd, the second by who had similarly written a 'key' to Swift's in 1705) were swiftly produced. These were mostly printed anonymously (or occasionally pseudonymously) and were quickly forgotten.

Swift had nothing to do with them and disavowed them in Faulkner's edition of 1735. Swift's friend wrote a set of five Verses on Gulliver's Travels, which Swift liked so much that he added them to the second edition of the book, though they are rarely included.Faulkner's 1735 edition In 1735 an Irish publisher, printed a set of Swift's works, Volume III of which was Gulliver's Travels. As revealed in Faulkner's 'Advertisement to the Reader', Faulkner had access to an annotated copy of Motte's work by 'a friend of the author' (generally believed to be Swift's friend Charles Ford) which reproduced most of the manuscript without Motte's amendments, the original manuscript having been destroyed. It is also believed that Swift at least reviewed proofs of Faulkner's edition before printing, but this cannot be proved. Generally, this is regarded as the of Gulliver's Travels with one small exception. This edition had an added piece by Swift, A letter from Capt. Gulliver to his Cousin Sympson, which complained of Motte's alterations to the original text, saying he had so much altered it that 'I do hardly know mine own work' and repudiating all of Motte's changes as well as all the keys, libels, parodies, second parts and continuations that had appeared in the intervening years.

This letter now forms part of many standard texts.Lindalino The five-paragraph episode in Part III, telling of the rebellion of the surface city of against the flying island of Laputa, was an obvious allegory to the affair of of which Swift was proud. Lindalino represented and the impositions of Laputa represented the British imposition of 's poor-quality copper currency.

Faulkner had omitted this passage, either because of political sensitivities raised by an Irish publisher printing an anti-British satire, or possibly because the text he worked from did not include the passage. In 1899 the passage was included in a new edition of the Collected Works. Modern editions derive from the Faulkner edition with the inclusion of this 1899 addendum.notes in The Annotated Gulliver that Lindalino is generally taken to be Dublin, being composed of double lins; hence, Dublin. Major themes. The King of Brobdingnag and Gulliver by (1803), (satirising and ).Gulliver's Travels has been the recipient of several designations: from to a children's story, from proto-science fiction to a forerunner of the modern novel.Published seven years after 's successful, Gulliver's Travels may be read as a systematic rebuttal of Defoe's optimistic account of human capability. In The Unthinkable Swift: The Spontaneous Philosophy of a Church of England Man, argues that Swift was concerned to refute the notion that the individual precedes society, as Defoe's novel seems to suggest. Swift regarded such thought as a dangerous endorsement of ' radical political philosophy and for this reason Gulliver repeatedly encounters established societies rather than desolate islands.

The captain who invites Gulliver to serve as a surgeon aboard his ship on the disastrous third voyage is named Robinson.Scholar Allan Bloom points out that Swift's critique of science (the experiments of Laputa) is the first such questioning by a modern liberal democrat of the effects and cost on a society which embraces and celebrates policies pursuing scientific progress. Swift wrote:The first man I saw was of a meagre aspect, with sooty hands and face, his hair and beard long, ragged, and singed in several places. His clothes, shirt, and skin, were all of the same colour. He has been eight years upon a project for extracting sunbeams out of cucumbers, which were to be put in phials hermetically sealed, and let out to warm the air in raw inclement summers.

He told me, he did not doubt, that, in eight years more, he should be able to supply the governor’s gardens with sunshine, at a reasonable rate: but he complained that his stock was low, and entreated me “to give him something as an encouragement to ingenuity, especially since this had been a very dear season for cucumbers.” I made him a small present, for my lord had furnished me with money on purpose, because he knew their practice of begging from all who go to see them.A possible reason for the book's classic status is that it can be seen as many things to many different people.

Maintaining me, although I had a very scanty allowance, being too great for anarrow fortune, I was bound apprentice to Mr. James Bates, an eminentsurgeon in London, with whom I continued four years. My father now andthen sending me small sums of money, I laid them out in learning navigation,and other parts of the mathematics, useful to those who intend to travel, as Ialways believed it would be, some time or other, my fortune to do.

When I leftMr. Bates, I went down to my father: where, by the assistance of him and myuncle John, and some other relations, I got forty pounds, and a promise ofthirty pounds a year to maintain me at Leyden: there I studied physic twoyears and seven months, knowing it would be useful in long voyages.Soon after my return from Leyden, I was recommended by my good master,Mr. Bates, to be surgeon to the Swallow, Captain Abraham Pannel,commander; with whom I continued three years and a half, making a voyageor two into the Levant, and some other parts.

When I came back I resolved tosettle in London; to which Mr. Bates, my master, encouraged me, and by him Iwas recommended to several patients. I took part of a small house in the OldJewry; and being advised to alter my condition, I married Mrs. Mary Burton,second daughter to Mr.

Edmund Burton, hosier, in Newgate-street, with whomI received four hundred pounds for a portion.But my good master Bates dying in two years after, and I having few friends,my business began to fail; for my conscience would not suffer me to imitatethe bad practice of too many among my brethren. Having therefore consultedwith my wife, and some of my acquaintance, I determined to go again to sea. Iwas surgeon successively in two ships, and made several voyages, for sixyears, to the East and West Indies, by which I got some addition to my fortune.My hours of leisure I spent in reading the best authors, ancient and modern,being always provided with a good number of books; and when I was ashore,in observing the manners and dispositions of the people, as well as learningtheir language; wherein I had a great facility, by the strength of my memory.The last of these voyages not proving very fortunate, I grew weary of the sea,and intended to stay at home with my wife and family. I removed from the OldJewry to Fetter Lane, and from thence to Wapping, hoping to get businessamong the sailors; but it would not turn to account. After three yearsexpectation that things would mend, I accepted an advantageous offer fromCaptain William Prichard, master of the Antelope, who was making a voyageto the South Sea.

We set sail from Bristol, May 4, 1699, and our voyage was atfirst very prosperous.It would not be proper, for some reasons, to trouble the reader with theparticulars of our adventures in those seas; let it suffice to inform him, that inour passage from thence to the East Indies, we were driven by a violent stormto the north-west of Van Diemen’s Land. By an observation, we foundourselves in the latitude of 30 degrees 2 minutes south. Twelve of our crewwere dead by immoderate labour and ill food; the rest were in a very weakcondition. On the 5th of November, which was the beginning of summer inthose parts, the weather being very hazy, the seamen spied a rock within half acable’s length of the ship; but the wind was so strong, that we were drivendirectly upon it, and immediately split.

Los Viajes De Gulliver

Six of the crew, of whom I was one,having let down the boat into the sea, made a shift to get clear of the ship andthe rock. We rowed, by my computation, about three leagues, till we were ableto work no longer, being already spent with labour while we were in the ship.We therefore trusted ourselves to the mercy of the waves, and in about half anhour the boat was overset by a sudden flurry from the north. What became ofmy companions in the boat, as well as of those who escaped on the rock, orwere left in the vessel, I cannot tell; but conclude they were all lost. For myown part, I swam as fortune directed me, and was pushed forward by wind andtide. I often let my legs drop, and could feel no bottom; but when I was almostgone, and able to struggle no longer, I found myself within my depth; and bythis time the storm was much abated. The declivity was so small, that I walkednear a mile before I got to the shore, which I conjectured was about eighto’clock in the evening. I then advanced forward near half a mile, but could notdiscover any sign of houses or inhabitants; at least I was in so weak acondition, that I did not observe them.

I was extremely tired, and with that,and the heat of the weather, and about half a pint of brandy that I drank as Ileft the ship, I found myself much inclined to sleep. I lay down on the grass,which was very short and soft, where I slept sounder than ever I rememberedto have done in my life, and, as I reckoned, about nine hours; for when Iawaked, it was just day-light. I attempted to rise, but was not able to stir: for,as I happened to lie on my back, I found my arms and legs were stronglyfastened on each side to the ground; and my hair, which was long and thick,tied down in the same manner. I likewise felt several slender ligatures acrossmy body, from my arm-pits to my thighs. I could only look upwards; the sunbegan to grow hot, and the light offended my eyes. I heard a confused noiseabout me; but in the posture I lay, could see nothing except the sky. In a littletime I felt something alive moving on my left leg, which advancing gentlyforward over my breast, came almost up to my chin; when, bending my eyesdownwards as much as I could, I perceived it to be a human creature not sixinches high, with a bow and arrow in his hands, and a quiver at his back.

In themean time, I felt at least forty more of the same kind (as I conjectured)following the first. I was in the utmost astonishment, and roared so loud, thatthey all ran back in a fright; and some of them, as I was afterwards told, werehurt with the falls they got by leaping from my sides upon the ground.However, they soon returned, and one of them, who ventured so far as to get afull sight of my face, lifting up his hands and eyes by way of admiration, criedout in a shrill but distinct voice, Hekinah degul: the others repeated the samewords several times, but then I knew not what they meant.

Los Viajes De Gulliver Pdf Libro De

I lay all this while,as the reader may believe, in great uneasiness. At length, struggling to getloose, I had the fortune to break the strings, and wrench out the pegs thatfastened my left arm to the ground; for, by lifting it up to my face, Idiscovered the methods they had taken to bind me, and at the same time with aviolent pull, which gave me excessive pain, I a little loosened the strings thattied down my hair on the left side, so that I was just able to turn my headabout two inches. But the creatures ran off a second time, before I could seizethem; whereupon there was a great shout in a very shrill accent, and after itceased I heard one of them cry aloudTolgo phonac; when in an instant I feltabove a hundred arrows discharged on my left h.